Hunting for New Worlds

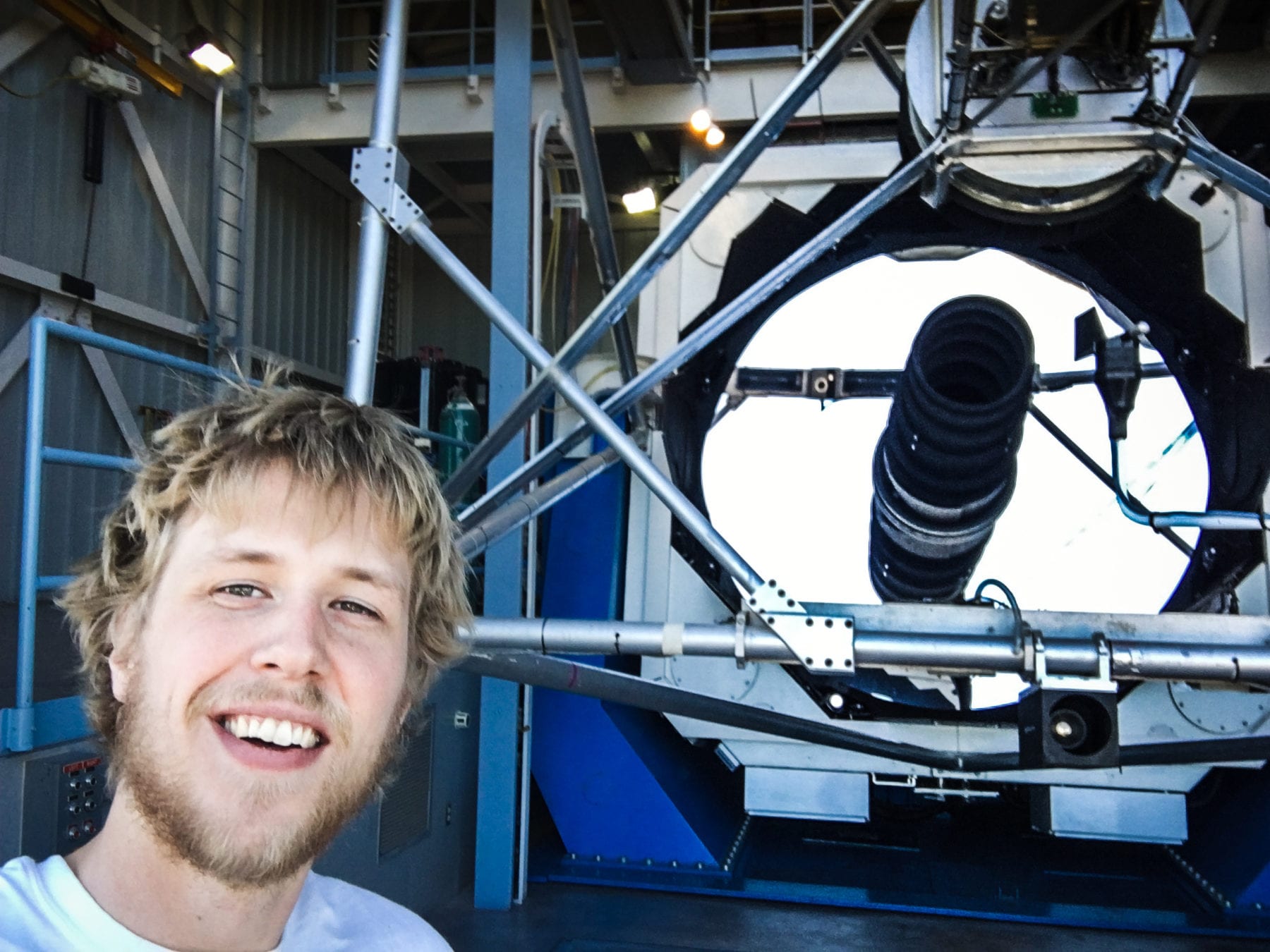

By Dr. Guðmundur Kári Stefánsson, Ph.D., Fulbright Fellow 2013-2014

Dr. Guðmundur Stefánsson completed his Ph.D. in astrophysics at Pennsylvania State University in 2019. As part of his PhD research, Guðmundur developed new instruments and technologies to better detect exoplanets—planets outside our solar system. His research has included the design and fabrication of two new planet-hunting spectrographs for NASA and the National Science Foundation. Guðmundur is currently a Henry Norris Russell postdoctoral fellow at Princeton University, where he is currently leading a number of scientific programs to detect and characterize nearby planetary systems. We asked Guðmundur to tell us about his current work and how his Fulbright experience has benefitted his research.

My research focuses on developing and using new technologies to better detect planets outside our solar system. This is a relatively new field of astrophysics that grapples with exciting fundamental questions: Which are the closest planets to Earth? Are any of them habitable? Do any of them contain life?

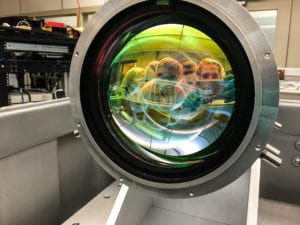

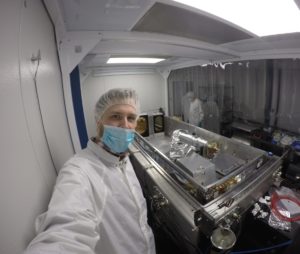

As part of my research, I have helped develop two next-generation planet-finding spectrographs—the Habitable-zone Planet Finder (HPF) for the 10m Hobby-Eberly Telescope at McDonald Observatory in Texas, and the NEID spectrograph we are currently commissioning on the 3.5m Telescope at Kitt Peak Observatory in Arizona.

Although completing a PhD is a multi-year process, it didn’t feel long. Time went by fast. There were projects to finish, classes to take, classes to teach, experiments to run, papers to write, conferences to attend, friends to meet, trails to hike, and places to see. It was a lot of fun.

On the research front, it was particularly fulfilling to be a part of a tightly-knit and supportive team of scientists and engineers working on cutting-edge projects from start to finish. We went from raw ideas on paper, through securing funding, cutting metal, extensive laboratory testing, which eventually culminated in delivery of our instruments at the observatory. After years of design and fabrication work and spending months testing the equipment at remote observatories, we are now actively discovering planets around nearby stars. Our two spectrographs are designed to be sensitive to detecting rocky planets in the Habitable-zone, the region around the star where a planet can sustain water in liquid form on its surface. In our most recent paper under review, we have detected a rocky planet orbiting a nearby star only 26 light years away, showing some of the first signatures of potential star-planet magnetic interactions. Exoplanets exhibiting such interactions have long been theorized to exist, but have remained undetected, so we are excited to be detecting one of the first planets showing evidence of such interactions. This planet is likely too hot to be in the Habitable-zone, but we have already detected a few other candidate signals that could suggest we might be finding new potentially habitable-planets. Stay tuned.

Receiving the Fulbright grant has been beneficial to my PhD and research career. First, the funds from Fulbright directly supported my living and travel expenses. Second, being a Fulbrighter provided recognition which helped secure future grants and fellowships to pay for specialized equipment. Perhaps most importantly, the Fulbright program provided me with a valuable network of inspiring colleagues and friends from all around the globe, many of whom I remain in active contact with today.

Before my PhD program began, I was invited to a Fulbright Gateway Seminar in Reno Nevada, a 5-day workshop bringing together ~60 new Fulbright students from all over the world starting their studies in the US. Even though we all came from different corners of the world, we immediately connected on our shared experience of embarking on a big journey in a new place. Even before I started my PhD, I had a network of friends and colleagues spread across all major cities and universities across the US—from software engineering and sustainable entrepreneurship on the West Coast, to international corporate management and genetic sequencing of mosquitoes on the East Coast.

I became particularly close with the local Fulbright Society at Penn State, attending numerous culture nights, open talks, United Nations-affiliated events, along with trips around Pennsylvania. I still keep in contact with my Penn State Fulbright friends, a number of which have had the chance to visit Iceland. We have now all finished our degrees, continuing our ambitions for the future across the world.

Throughout my time spent in the US, I am often the first Icelander people meet. This comes with a responsibility to represent and share Icelandic culture and perspectives on numerous occasions. In the last year of my PhD, I helped organize Extreme Solar Systems IV 2019, an exoplanet conference affiliated with the American Astronomical Society, which we held in the Harpa Conference Center in Reykjavík.

The meeting was the biggest conference held in exoplanet science to date, with over 600 attendees, giving talks and poster presentations on the latest news in exoplanet science. In the last weeks of my PhD, we had come full circle: I now got to show everyone Icelandic food, scenery, and culture, which I had told them so emphatically about throughout my PhD.

Among the presenters at the conference was Didier Quezloz, who a few days later received the 2019 Nobel Prize in Physics for his discovery of the first exoplanet orbiting a star like the Sun. During his visit at Penn State, just a few days after the announcement, I was fortunate enough to get the chance to go to dinner with him to hear his stories of the early days of exoplanet finding and the brewing excitement he has for future exoplanet science missions.

I chose to do a PhD in astrophysics at Penn State, as I knew they were working at the forefront of the new field of exoplanet science. Receiving the Fulbright grant helped me get to where I am today, and I am thankful for that. The future is bright in exoplanet science, with hundreds of new planet candidates that need further characterization, with thousands more expected to be detected in the near future. Now it is just a question of when we might be able to detect the signatures of biological processes on these new worlds. I am excited to help uncover some of the answers.”